Yale’s Ties to Slavery Confronting a Painful History, Building a Stronger Community

Introduction

Founded in 1701, Yale has a complex past that includes direct and indirect ties to slavery. That history cannot be remade. What can be done is to reveal, share, and learn from that history, so we can strengthen our community and advance Yale’s mission of education and research to create a better future.

To that end, Yale in 2020 launched the Yale and Slavery Research Project to study the institution’s historical involvement with slavery. The discoveries made by the project’s historians and scholars were made public and addressed by Yale throughout the research process. You will find on this website much of what the team learned. For those who wish to know more, we encourage you to read the full account in Yale and Slavery: A History, by Sterling Professor of History David W. Blight with the Yale and Slavery Research Project.

In the webpages that follow, you will also be able to discover what Yale has done, is doing, and will continue to do to address the legacy of slavery.

History

Yale was founded three-quarters of a century before the United States declared its independence. Most of its ten founding trustees owned enslaved people. From that point onward, Yale’s history often reflects—for good and for ill—the history of the country.1636

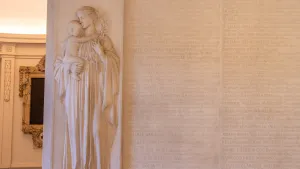

Violence between Pequots and English colonists intensifies in areas surrounding Long Island Sound. Disease, displacement, and warfare have taken a toll on Indigenous communities. By this time, the Pequot population has declined by nearly 80 percent to around 3,000 people. Pequot culture and security are under tremendous threat.

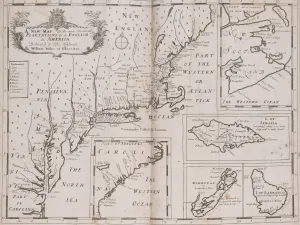

Map of New England, Yale University Library.

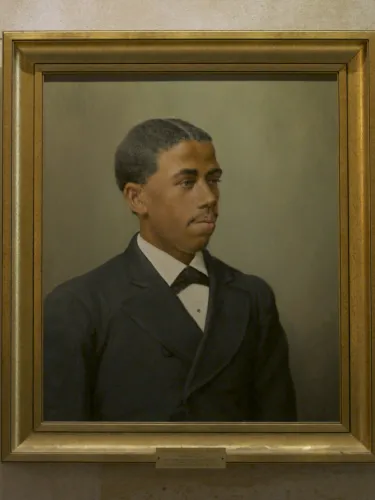

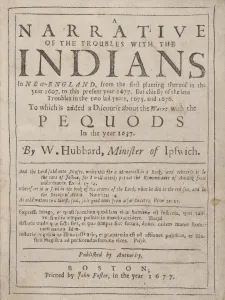

1637 May

English troops with some Native allies massacre an entire village of 400 Pequot men, women, and children in their fort near the Mystic River. “The fires… in the centre of the fort blazed most terribly,” writes a captain in the English force, “and burnt all in the space of half an hour.”

William Hubbard, “A narrative of the troubles with the Indians in New-England…” Yale University Library.

1638

The first known Africans in Massachusetts, purchased with proceeds earned by selling Pequot captives, arrive on a ship with cotton and tobacco. This trade continues, and in 1646, the New England Confederation codifies that Native captives should “be shipped out and exchanged” for enslaved Black people.

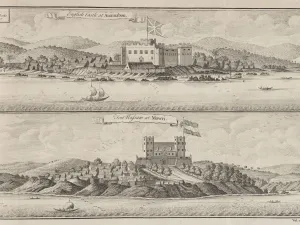

English Castle at Anamabou, Yale University Library.

1638 April

New Haven Colony, led by John Davenport and Theophilus Eaton, is founded.

The Reverend John Davenport, Yale University Art Gallery.

1638 September

The Treaty of Hartford is forced upon the Pequots, designed to both humiliate and liquidate them as a people. The term “Pequot” is outlawed and the Pequot people are declared extinct (though they still survive until today). The first Africans in the Connecticut colony, meanwhile, likely arrive during the Pequot War, probably in trade for Indigenous people who are taken prisoner and enslaved.

1639

Although it is uncertain exactly when the first Africans arrive in Connecticut, their presence is initially recorded at this time, when an enslaved Black boy named Louis Berbice, from Dutch Guiana, is killed by his owner in Hartford. Africans may have been present in New Haven even earlier, likely from its founding; Lucretia, a Black woman, belonged to the colony’s founder and governor, Theophilus Eaton, and may have arrived with him.

1662

New Haven Colony is incorporated into the larger colony of Connecticut.

1675

King Philip’s War breaks out, pitting Native inhabitants of coastal Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut against English colonists supported by some Indigenous allies. The war is fought over land and water, but also stems from hatred and fear among the English that, in living so close to people they consider barbarous, they are losing their faith and purpose. Many Natives, for their part, have come to loathe the English for their greed, arrogance, and conquests; many Indigenous leaders, or sachems, also fear the conversion to Christianity of some of their rival neighbors. Despite opposition from some (not all) clergy, kidnapping and a regional slave trade in Native refugees intensifies as a profitable business during and after the war.

1676 August

A Native marksman serving the English kills King Philip, a sachem of the Wampanoag of southeastern Massachusetts whose real name is Metacom. The sachem’s body is dismembered and decapitated, and his body parts are circulated as mythic objects by English colonists for years to come. His son is one of countless Native children sold into slavery by the English.

Image above: A 19th century depiction of Metacom, known to the English settlers as “King Philip,” Yale University Library.

1690

The Connecticut Colony bans Black and Indigenous people from occupying public roadways after 9 p.m.

1700

On the eve of the creation of the Collegiate School that would become Yale, one in 10 property inventories in the colony of Connecticut includes enslaved people.

1701 October 9

The General Assembly in New Haven authorizes the creation of a college and names 10 clergymen as trustees. The following month, seven of those ministers gather in Saybrook, Connecticut, for their first meeting. Enslaved people are likely present; at least seven of the 10 minister-trustees owned enslaved people. An early 20th-century history of Yale College describes the clergymen as “followed on horseback by their men-servants or slaves, into old Killingworth Street.”

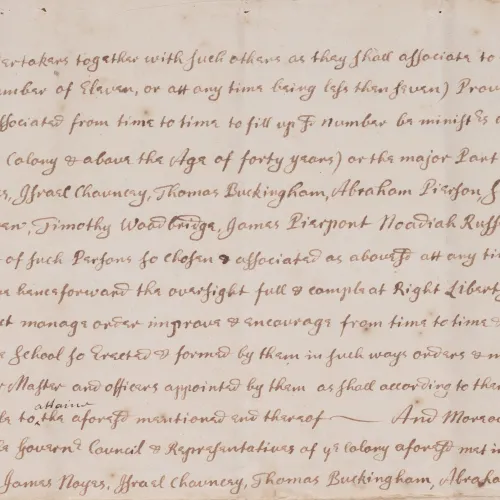

Image above: 1701 Yale Charter, Yale University Library.

Images below, left to right: A New Map of the Most Considerable Plantations of the English in America. Dedicated to His Highness William Duke of Glocester, Yale University Library; Portrait of Mary Hooker Pierpont, Yale University Art Gallery.

1713–1721

Elihu Yale, a wealthy Bostonian who had moved to England as a child, sends hundreds of books, a portrait of King George I, and “goods and merchandizes” to support the Collegiate School of Connecticut. Some portion of Elihu Yale’s fortune is derived from his commercial entanglements with the slave trade; as the governor of Madras, India, for the East India Company, he had a direct role in the trafficking of enslaved people.

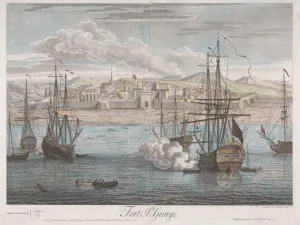

Images, left to right: Elihu Yale Snuffbox, Yale University Art Gallery; Elihu Yale with His Servant, Yale University Art Gallery; Fort St. George, Yale Center for British Art; Elihu Yale, Yale University Art Gallery.

1716

Thirteen-year-old Jonathan Edwards begins his studies in Wethersfield, Connecticut, just south of Hartford, one site where Collegiate School students are educated at the time. That same year, the Collegiate School, after conducting classes in Saybrook, Wethersfield, and other Connecticut towns for more than a decade, moves permanently to New Haven.

1717–1718

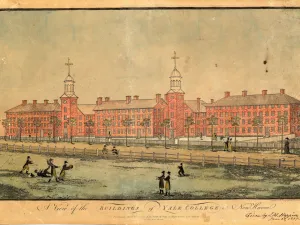

In honor of the contributions of Elihu Yale—and to entice him to make additional donations—the Collegiate School constructs a building called “Yale College.” This house, the first school building for instruction in New Haven, stands three stories high, 170 feet long, and 22 feet wide, and contains some 50 studies for students.

Elihu Yale with Members of his Family and an Enslaved Child, Yale Center for British Art.

1718 September 12

Yale College holds a “splendid Commencement” ceremony, presided over by Connecticut governor Gurdon Saltonstall, a passionate defender of slavery. From this day forward, the third-oldest institution of higher learning in America is known as Yale.

Image above: First Commencement, Held in 1718, Yale University Library.

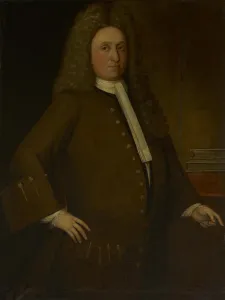

Image below: Governor Gurdon Saltonstall, Yale University Art Gallery.

1720

Jonathan Edwards receives his baccalaureate degree from Yale College. Over the nearly four decades that follow, he becomes America’s most renowned theologian.

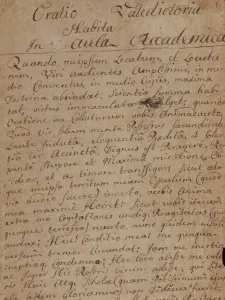

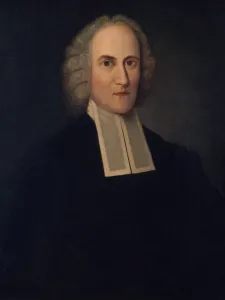

Images, left to right: Valedictory Oration, in Latin, delivered at the Yale College commencement of September 1720, Yale University Library; Jonathan Edwards, Princeton University Art Museum.

1721

As Yale expands, much of its funding comes from commerce dependent on enslaved labor—including the West Indies rum business. The Connecticut General Assembly this year passes “An Act for the better Regulating the Duty of Impost upon Rhum,” which includes the provision, “That what shall be gained by the impost on rum for two years next coming shall be applied to the building of a rectors house for Yale College.”

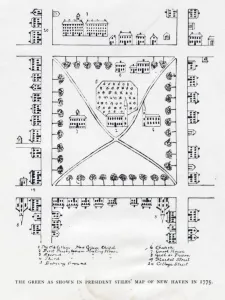

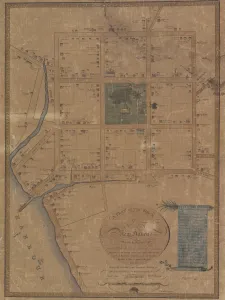

Map of New Haven, Yale University Library.

1730

The Connecticut Colony passes a law stating that Black, Indigenous, or mixed-race people would be “whipped with forty lashes” if they “uttered or published… words” about a white person that were deemed “actionable” under law. At this time, Africans number roughly 700 out of 38,000 people in Connecticut, or 1.8 percent of the population.

1739

Jonathan Edwards surmises that a few hundred years hence, “Negroes and Indians will be divines,” and will write “excellent books,” become “learned men,” and “shall then be very knowing in religion.” Although he condemns slave trading in the Atlantic, he and his wife enslave several Black people. Edwards never opposes the ownership of enslaved Africans in his community or his household, which serves as a model of behavior for many other Yale leaders and graduates.

1745

Philip Livingston Sr. a businessman and human trafficker, donates the considerable sum of £28, ten shillings to Yale College in recognition of the education his sons have received there. The Livingston fortune is derived in part from investments in slave ships transporting hundreds of Africans from the continent to forced labor in the Americas, and from the provisioning of plantations in the Caribbean. In 1756, Livingston’s gift becomes the basis for the Livingstonian Professorship in Divinity, the college’s first professorship and one of its most prestigious for many years.

Robert Livingston, Yale University Library.

1749

The Black population of the Connecticut Colony reaches 1,000, a number that will grow to 3,587 by 1756.

A plan of the town of New Haven with all the buildings in 1748… Yale University Library.

1750 April 17

The first stone is laid in the construction of Connecticut Hall. This prized work of architecture—now the oldest surviving brick structure in the state—is built in part by Black workers enslaved by Yale luminaries.

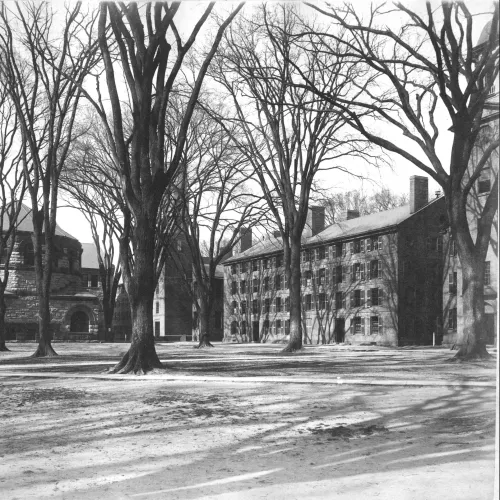

Image above: Osborn Hall and South Middle College, Yale University Library.

Images below, left to right: Plan of the City of New Haven, Yale University Library; Connecticut Hall ca. 1930s, Yale University Library; Connecticut Hall ca. 1890s, Yale University Library.

1773

James Hillhouse graduates from Yale. He will go on to serve in the state legislature, the U.S. House of Representatives, and the U.S. Senate, and will leave his mark on both Yale and New Haven, helping design Old Brick Row, draining and beautifying the New Haven Green, organizing Grove Street Cemetery, and serving as Yale’s treasurer for 50 years. Though he takes public stances against slavery, he and his wives own enslaved people.

Images, left to right: A view of Old Brick Row, including Connecticut Hall, Yale University Library; James Hillhouse, Yale University Library; Elevations and Plans of Present and Projected buildings of Yale College by John Trumbull, Yale University Library.

1773

Jonathan Edwards, Jr., son of the famous theologian, writes a series of five articles anonymously in The Connecticut Journal and the New-Haven Post-Boy, entitled “Some Observations on the Slavery of Negroes.” The articles establish a theological basis for the antislavery cause, challenging slavery and the slave trade as Christian hypocrisy.

1774

The Connecticut colony outlaws further importation of enslaved people into its borders, a statute not easily enforced. A census the same year counts 6,464 Black people in Connecticut, the largest number in any New England colony, representing 3.2 percent of the population. New Haven County contains 854 enslaved people, and the town of New Haven records 262 people held in bondage.

1774 October

In Connecticut, “a humble petition of a number of poor Africans,” signed by Bristol Lambee on behalf of many others, asks for “deliverance from a state of unnatural servitude and bondage.” The petitioners assert “that LIBERTY, being founded upon the law of nature, is as necessary to the happiness of an African, as it is to the happiness of an Englishman.” Lambee and his friends beg those inclined toward revolution against Great Britain to “hear our prayers.” Just as the revolutionaries of the colony protest those who “would subject you to slavery,” they write, African Americans demand that those same revolutionaries reflect upon their own “unnatural custom” of holding people as property.

John Trumbull, The Battle of Bunker’s Hill, June 17, 1775, Yale University Art Gallery.

1776

Samuel Hopkins, Yale Class of 1741, delivers a sermon appealing to the consciences of American patriots. “Rouse up then my brethren and assert the Right of universal liberty;” Hopkins declares, “you assert your Right to be free in opposition to the Tyrant of Britain; come be honest men and assert the Right of Africans to be free in opposition to the Tyrants of America.”

Samuel Hopkins, The New York Public Library.

1776

In the year of American political independence, fully one-quarter of wills probated in Connecticut include enslaved property.

1776

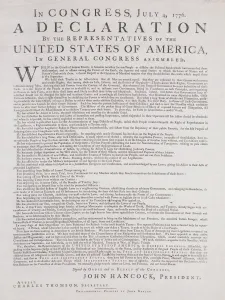

Signing of the Declaration of Independence begins. Four of the signatories are Yale graduates—Philip Livingston (New York), Lewis Morris (New York), Oliver Wolcott (Connecticut), and Lyman Hall (Georgia)—all of whom are enslavers.

Dunlap Broadside of the Declaration of Independence, Yale University Library.

1779

Two enslaved men, Prince and Prime, submit a petition to the state General Assembly demanding their freedom in the name of both Enlightenment doctrine and Christian virtue.

1779

The British invade New Haven.

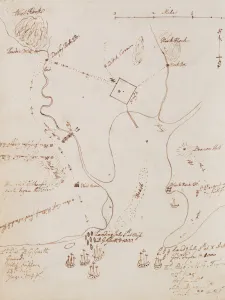

Images, left to right: Sketch of the British Invasion of New Haven from Ezra Stiles Papers, Yale University Library; Ezra Stiles, Yale University Art Gallery; Map of the British Invasion, Yale University Library; New Haven Green, Yale University Library.

1784

The state of Connecticut enacts a gradual abolition law, stating that anyone born to enslaved parents after March 1, 1784, would become free on their 25th birthday. An addition in 1797 changes the age to 21 for girls.

1786

Jupiter Hammon, a man enslaved by the Lloyd family of Long Island—relatives by marriage to James Hillhouse, in whose New Haven home he spent time—writes a poem, “An Essay on Slavery”—a revelatory work of Christian devotion and moral condemnation of slavery. Hammon is today recognized as the first published African American poet.

Image above: A View of Old Brick Row, Including Connecticut Hall, Yale University Library.

Image below: Yale College and the College Chapel, Yale University Library.

1790

The population of enslaved people in New Haven is declining. The county contains 433 enslaved people, a little more than half the number 16 years earlier. The town of New Haven includes 76 enslaved people, less than a third of the number in 1774.

1790 October 20

Joseph Mountain, a 32-year-old Black man, is convicted of rape and hanged on the New Haven Green. A reported crowd of 10,000 people, more than twice New Haven’s population, gathers to watch the spectacle. Mountain’s notoriety traveled broadly thanks to a purportedly autobiographical account of the crime, Sketches of the Life of Joseph Mountain, likely ghostwritten by David Daggett (Yale 1783), one of the future founders of the Yale Law School. Daggett claimed to have only taken dictation, but he was the magistrate who recorded the confession and saw that it was published. The popular text widely disseminated ideas of Black criminality, threats to social order, and propensities to sexual violence.

1792

The Connecticut state legislature passes a law forbidding enslavers from selling their human property outside of the state.

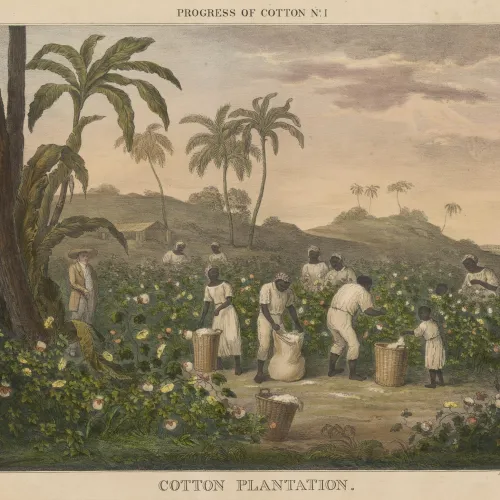

1794

Eli Whitney, a recent graduate of Yale, obtains a patent for a new type of cotton gin. The innovation revolutionizes cotton production and fuels slavery’s expansion in the South.

Image above: The Eli Whitney Gun Factory, Yale University Art Gallery.

Image below, left to right: Drawing of a Mechanical Cotton Gin, Yale University Library; Eli Whitney, Yale University Art Gallery.

1795

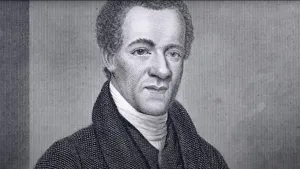

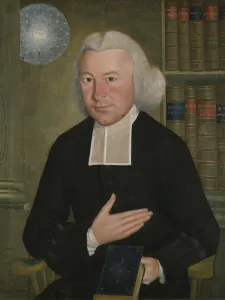

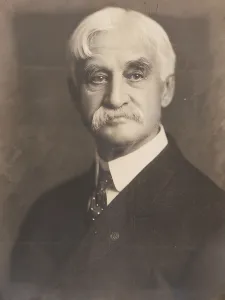

Timothy Dwight, an enslaver and a minister who regards antislavery activities as socially disruptive, succeeds Ezra Stiles as president of Yale College.

Timothy Dwight, Yale University Art Gallery.

1800

The United States produces 36.5 million pounds of cotton, up from 1.5 million pounds produced a decade before. The number of enslaved people in the United States grows to 908,000, up from roughly 700,000 in 1790—and continues to increase significantly along with the expansion of cotton production.

Image above: Drawing from an 1840 Book Showing Enslaved Black People Picking Cotton, Yale University Art Gallery.

1804

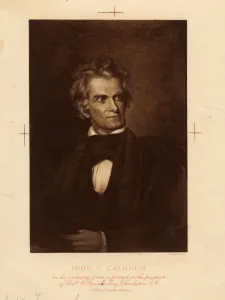

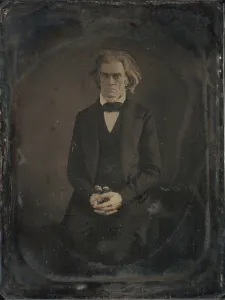

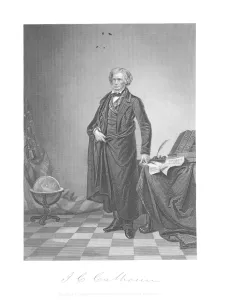

John Caldwell Calhoun of South Carolina graduates from Yale, after which he studies law for one year. He becomes an influential congressman, senator, secretary of war, secretary of state, presidential candidate, and vice president—as well as a zealous protector of the “minority rights” of enslavers and a proponent of slavery as a “positive good.”

Images, left to right: John C. Calhoun Portrait, Daguerreotype of John C. Calhoun, John C. Calhoun Portrait, Stained Glass Window of John C. Calhoun, A. B. Doolittle Engraving of Yale College, Yale University Library.

1814

Connecticut’s General Assembly passes legislation formally prohibiting Black men from voting. Despite eloquent petitions from Black New Haveners William Lanson and Bias Stanley, the restrictions are incorporated into the Connecticut constitution of 1818.

1816

The American Colonization Society (ACS) is formed in Washington, D.C. It fosters a scheme to send willing Black Americans to the new colony of Liberia on the west coast of Africa and develops a popular following across the U.S. political spectrum.

1817

Jeremiah Day, a staunch social and religious conservative, becomes president of Yale. He presides during a period when the divinity and law schools are founded.

Jeremiah Day, Yale University Art Gallery.

1820

Black residents of New Haven come together with Simeon Jocelyn, a white man, to form a separate Black congregation, soon known as the African Ecclesiastical Society. In 1829, it receives formal recognition as a Congregational church and is known as the Temple Street Congregational Church, a center of Black education, abolitionism, and community life in New Haven.

1825

The last sale of enslaved people in New Haven takes place on the New Haven Green. The buyer is an abolitionist, Anthony P. Stoddard, who immediately frees Lois and Lucy Tritton, a mother and daughter.

John Warner Barber, New Haven Green, 1825, Yale University Library.

1825

William Grimes, living in New Haven and running a shop near the Yale campus, authors the first published narrative by an American-born slave: Life of William Grimes, the Runaway Slave, Written by Himself.

1827

Leonard Bacon, an 1820 graduate of Yale, together with prominent Yale graduate and science professor Benjamin Silliman Sr. establish the Connecticut branch of the American Colonization Society.

1831

William Lloyd Garrison, a white Bostonian, begins publishing the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator.

1831 August 7

A group calling itself the Peace and Benevolent Society of Afric-Americans meets in New Haven and unanimously passes a set of resolutions condemning efforts to push Black people to move to Africa. “Resolved, That we know of no other place that we can call our true and appropriate home,” one resolution reads, “excepting these United States, into which our fathers were brought, who enriched the country by their toils, and fought, bled and died in its defence, and left us in its possession—and here we will live and die…”

1831 September 10

An abolitionist alliance, with $10,000 from Black donors and $10,000 from white donors, prepares to build in New Haven the first college for Black men in the United States. In response, New Haven Mayor Dennis Kimberly, a Yale graduate, hosts an “extraordinary meeting” of white property owners “to take into consideration a scheme (said to be in progress) for the establishment, in this City, of ‘a College for the education of Colored Youth.’” At the packed whites-only meeting, 700 people oppose the college and only four vote in favor. The plan is thwarted.

Engraving of Yale College Scene by S. S. Jocelyn, Yale University Library.

1833 May 24

The Connecticut state legislature passes what becomes known as the “Connecticut Black Law,” preventing Black people from outside of the state from being educated in Connecticut.

1834

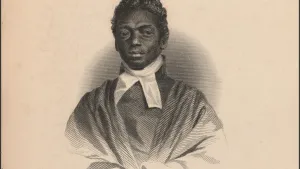

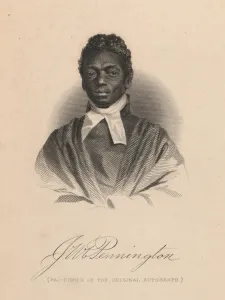

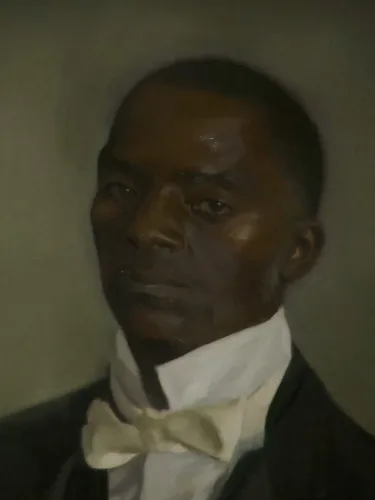

James W. C. Pennington becomes the first Black person known to attend classes at Yale. Pennington, who had escaped from slavery on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, was denied formal admission on account of his race, but he was allowed to be a “visitor” at the Yale divinity school. “My voice was not to be heard in the classroom asking or answering a question,” Pennington later wrote. “I could not get a book from the library and my name was never to appear on the catalogue.”

Image above: Yale College, J. W. Barber’s View, Yale University Library.

Image below: The Reverend James W. C. Pennington, National Portrait Gallery.

1837

Samuel F. B. Morse, the famous inventor, artist, and one of Yale’s most notorious proslavery advocates of the antebellum and Civil War eras, tests his first telegraph. He spurs a technological revolution but rejects the principles of democracy and abolition. By the early 1850s he defends slavery as “a social condition ordained from the beginning of the world for the wisest purposes, benevolent and disciplinary, by Divine Wisdom.”

Images, left to right: Foreign Conspiracy Against the Liberties of the United States, Library of Congress; Samuel F. B. Morse, Yale University Library.

1837

The Reverend Amos Gerry Beman becomes pastor of the Temple Street Church. Beman, a national leader of antislavery, temperance, suffrage, and other reform efforts, serves the church for two decades. His scrapbooks document a rich period of organizing and activism in New Haven’s Black community.

1839

Southern students make up roughly 10 percent of the Yale student body, and their numbers continue to grow. “Yale was the favorite college of the southern planters,” wrote Julian Sturtevant, an 1826 graduate, in a later memoir. “From the days of John C. Calhoun, almost to the war of the rebellion, the number of southern students was large.”

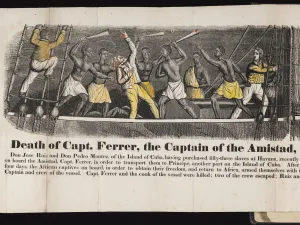

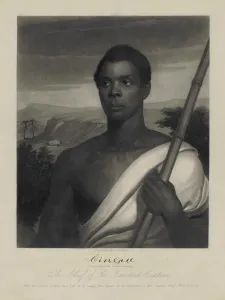

1839 June 30

Enslaved Africans aboard the slave-trading vessel La Amistad revolt and take over the ship. After a tortuous journey in which several captives die of hunger and disease, the ship is eventually captured by the U.S. Navy and brought to New London, Connecticut. The Africans are put on trial in New Haven, becoming the focus of both local and national attention.

Images, left to right: Death of Capt. Ferrer, the Captain of the Amistad, Yale University Library; Cinque: The Chief of the Amistad Captives, Yale University Art Gallery.

1841 March 9

The Africans who survived the Amistad ordeal, backed by abolitionists—including some Yale graduates and students—win their case before the Supreme Court. The Court denies Spanish claims to ownership over the Africans, who are set free. The verdict, however, does not challenge the underpinnings of slavery where it is legal in the United States.

1841 November 26

Thirty-five surviving Amistad rebels, along with five missionaries, board a vessel in New York Harbor to begin a voyage to Sierra Leone. Their eventual homecomings are difficult. Most shed their Western clothes to the chagrin of the missionaries who accompany them. Some find their parents and other family members and experience emotional reunions. Yet they soon find themselves back in an African society ravaged by war and slave-trading.

1846 October 21

Theodore Dwight Woolsey becomes president of Yale, serving in that position until 1871.

Reverend Theodore D. Woolsey, President of Yale College, Yale University Library.

1850 September 18

Congress passes the Fugitive Slave Act, requiring that enslaved people be returned to their owners even if they reside in a free state. One of a series of compromises meant to forestall disunion, the legislation is a turning-point for some moderate abolitionists from Yale who become more committed to antislavery causes.

1857

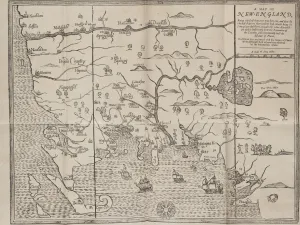

Cortlandt Van Rensselaer Creed receives an MD from Yale, becoming the first known Black person ever to graduate from the medical school. (Richard Henry Greene graduates from Yale College in the same year.) Creed’s family has deep roots in New Haven.

1858

The fiercely pro-slavery merchant Joseph Sheffield purchases the old Medical Department building on College Street in New Haven, adds two wings, and remodels the entire structure. With a supporting gift of $50,000 for “the maintenance of Professorships of Engineering, Metallurgy, and Chemistry,” Sheffield makes Yale a training center for scientists. Over time, Sheffield’s financial gifts to Yale reach $1.1 million, a figure not matched by any Yale donor until well into the 20th century.

Images, left to right: Sheffield Mansion, Yale University Library; Joseph Earl Sheffield, Yale University Art Gallery; Joseph Earl Sheffield, Yale University Library.

1860

On the eve of the Civil War, the number of enslaved people in the United States reaches nearly four million people.

1861

During the war, virtually no Southerners remain enrolled at Yale. By the end of the war, according to one authoritative account, 511 Yale men have served the Confederacy as soldiers and civil officials, of whom 55 die in the war. Among Yale Confederates, 68 are from Northern states; Connecticut contributes an astonishing 28 Yale men who serve the Confederate cause. There is no definitive account of how many Yale students and alumni serve in the Union Army, but researchers have estimated that total at roughly 700 to 850 men.

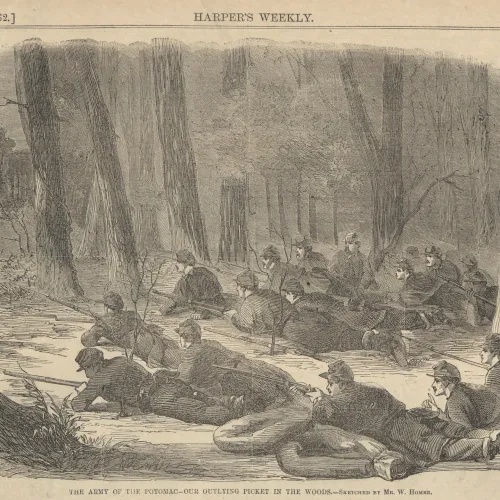

Image above: The Army of the Potomac — Our Outlying Picket in the Woods, from Harper’s Weekly, Yale University Art Gallery.

1861 April 12

Confederate troops fire on Fort Sumter in South Carolina’s Charleston Harbor—the first shots of the Civil War.

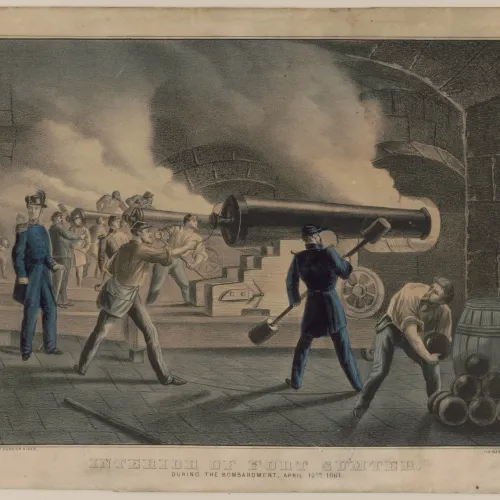

Image above: Interior of Fort Sumter: During the Bombardment, April 12, 1861, Library of Congress.

1861 June 10

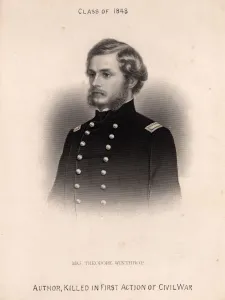

Theodore Winthrop, Yale class of 1848 and President Woolsey’s nephew, becomes the first Yale death in Civil War combat. His killing in eastern Virginia at the battle of Big Bethel, an early and humiliating Union defeat, is reported by the Yale Literary Magazine 10 months later. He is buried in Grove Street Cemetery.

Theodore Winthrop, Yale University Library.

1863

Official recruiting of Black soldiers to the Union Army and Navy begins. Before war’s end, they number nearly 200,000, including both former slaves from the South and free men of the North.

1863 January 1

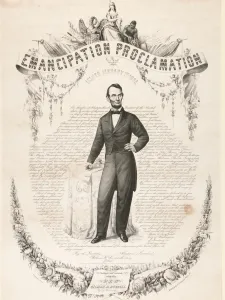

President Abraham Lincoln issues the Emancipation Proclamation, which declares that all enslaved people within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.”

Emancipation Proclamation, Yale University Art Gallery.

1863 November

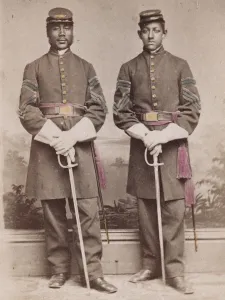

The Connecticut General Assembly authorizes the organization of an African-American regiment to fight in the Civil War; Governor William A. Buckingham thereupon calls for the recruitment of the Twenty-Ninth Connecticut Volunteers. Black men from some 119 towns and cities around Connecticut ultimately enlist.

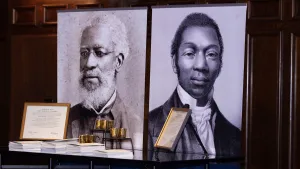

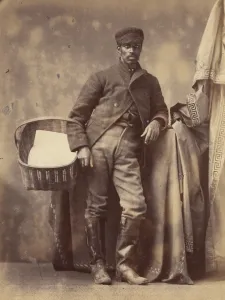

Alexander Herritage Newton (left), Quartermaster Sergeant, and Daniel S. Lathrop, Quartermaster Sergeant, both of the Twenty-Ninth Regiment Connecticut Volunteers, Yale University Library.

1864 August

The New York Times attacks Yale for its alleged “draft-shirking,” accusing Yale students and their faculty and administration of “plotting evasion and desertion.” At the college, claims the Times, “how to escape the draft” is the issue of the day. “The gutters are dragged for substitutes… Negro slaves who owe to the Republic nothing but curses, are driven to the rescue.”

Image above: Soldiers Assembled on the New Haven Green, Yale University Library.

1865 April 9

Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrenders to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, symbolizing the end of a long and bloody civil war.

1869

Ebenezer Don Carlos Bassett is appointed United States Minister Resident to Haiti, becoming the nation’s first Black diplomat. He had studied at Yale and was the first Black graduate of the State Normal School. Two of his sons go on to attend Yale, including Ulysses Simpson Grant Bassett, Class of 1895, named for the president who appointed his father to the diplomatic service.

Ebenezer Don Carlos Bassett Jr., Yale University Library.

1871 April

Congress passes the Third Enforcement Act, also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871, which enables the president to suspend habeas corpus in his efforts to combat the KKK and rein in what was beginning to seem like a second civil war.

1871 April 10

Mary A. Goodman signs her last will and testament, leaving her entire estate, except a small annual bequest to her father, to the Yale Theological Department to “be used in aiding young men in preparing for the Gospel ministry, preference being always given to young men of color.” Goodman had worked her entire life in domestic service and as a washerwoman taking in laundry. But when she died in 1872, her real and personal property was worth the substantial sum of about $5,000.

1874

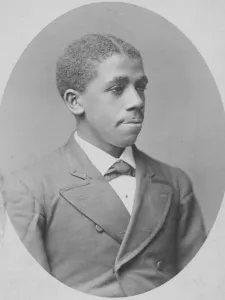

James W. Morris becomes the first Black student to graduate from the Yale Theological Seminary. His contemporary Solomon M. Coles, born enslaved in Virginia, matriculated first but graduated a year later. Coles was the first African American student to complete the entire three-year course of study in theology at Yale.

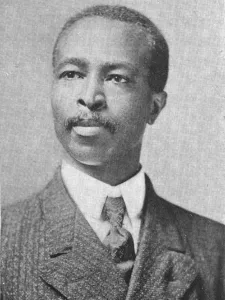

Solomon M. Coles, Blackpast.org.

1875

Bayard Thomas Smith graduates from Yale’s medical school. His fellow student George Robinson Henderson, who like Smith transferred to Yale from Lincoln University, a Black institution in Oxford, Pennsylvania, graduates a year later. Smith and Henderson are the first Black graduates of the Yale medical school since Cortlandt Van Rensselaer Creed graduated in 1857—a hiatus of nearly 20 years.

1876

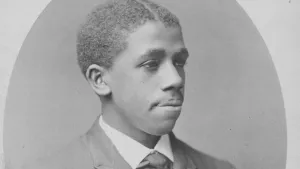

New Haven native Edward Bouchet, just two years after finishing his bachelor’s degree at Yale, earns his PhD in physics from Yale. He is the first African American to earn a PhD in any subject in the United States and only the sixth person of any background or race to earn a PhD in physics from an American university. His research delves into geometrical optics and refraction in glass.

Edward Alexander Bouchet, Yale University Library.

1880

Edwin Archer Randolph becomes the first Black graduate of Yale Law School. He is also the first African American admitted to practice law in Connecticut, although he never does. Instead, after graduation he moves to Virginia where he goes into private practice, is elected to political office, and founds the Richmond Planet, a Black newspaper.

Edwin Archer Randolph, Yale University Library.

1881

John Wesley Manning, an early Black student whose parents escaped slavery in North Carolina, graduates from Yale College. Like many other academically gifted Black graduates, he spends his post-graduate career working at segregated schools. After moving to Tennessee, he teaches Latin and serves as the principal of a school in Knoxville. Active in church and civic affairs, Manning holds leadership positions in the East Tennessee Association of Teachers in Colored Schools and the Tennessee Conference of Educational Workers and participates in the Southern Sociological Congress in 1915.

John Wesley Manning, Yale University Library.

1883

Henry Edward Manning, brother of John Wesley Manning, receives a three-year certificate from the Yale School of Fine Arts. (The art school did not begin granting degrees until 1891.) Manning may have been the first Black student to receive a certificate from the Yale art school. After graduation, he teaches drawing at a school in Knoxville, Tennessee, and at Allen University in Columbia, South Carolina, but he spends most of his career as a sign painter in New Haven. In the 1920 census, he is listed as self-employed, owning his own business and his own house.

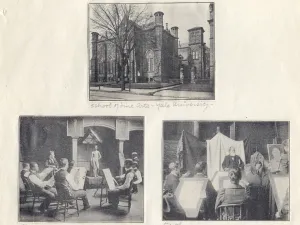

Photographs of Classes, Including for Art, Yale University Library.

1884

Thomas Nelson Page published his story “Marse Chan,” one of his most popular works offering a sentimental vision of antebellum Southern life, depicting slavery as benevolent and enslaved people as unwaveringly loyal to their enslavers. Part of a national turn toward reconciliation, in which the advances of Black rights during Reconstruction were viewed as a terrible mistake, Page’s writing received glowing reviews in the Yale Daily News, and he was invited to speak on campus.

1884

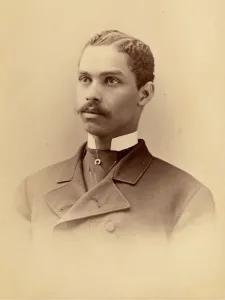

A statue of Yale science professor Benjamin Silliman Sr. is unveiled on campus. His “faithful” associate Robert M. Park, a free Black man who contributed to Silliman’s work, is on hand to draw aside the veil. Park’s commitment to movements for Black rights paid some dividends in his lifetime: He lived to see one of his grandchildren, Ulysses S. Grant Bassett, graduate from Yale only months before he died.

Ulysses Simpson Grant Bassett, Yale University Library.

1886

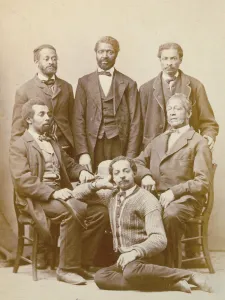

Student publications and alumni reminiscences, including Sketches of Yale Life, published this year, often feature racist and derogatory accounts of Black custodians and “campus characters.” These men made their living by cleaning dormitories or selling candy and other goods to Yale students. They had lives beyond their work at Yale of which most students were unaware.

Images, left to right: Candy Vendor Theodore Ferris; Candy Vendors Theodore and Mary Ferris; Candy Vendor Hannibal Silliman; Custodian John Jackson; Yale Custodians Osborn Allston, Isom Allston, John Jackson, and George Livingston; A Group of Yale Custodians, Including Isom Allston and George Livingston; Custodian Osborn Allston, Yale University Library.

1890

The Southern Club is established at Yale, open to “all men whose homes are or were south of the old Mason and Dixon line.” Five years later, the club occupies an entire page of the Yale Banner yearbook, with a long list of members and a racist cartoon featuring a buffoonish Black figure.

1896 June

The Reverend Joseph Twichell—an 1859 graduate of Yale College, longtime member of the Yale Corporation, and close friend of Mark Twain—speaks at the dedication of a new statue commemorating former Yale President and Union stalwart Theodore Woolsey. Hearing that the senior class aims to plant, as its “class ivy,” a sprig from the grave of Robert E. Lee, Twitchell is horrified. He tells the gathering that Woolsey’s face would, if it could, be “averted from the scene.”

Joseph Twichell, Yale University Library.

1897

The Sheffield Debating Club at Yale decides to address the topic, “Resolved: That lynching is justifiable.” Two debaters take the affirmative position and two the negative. The judges and “the house” decide in favor of the affirmative. The same year, more than 120 Black people are lynched in the United States.

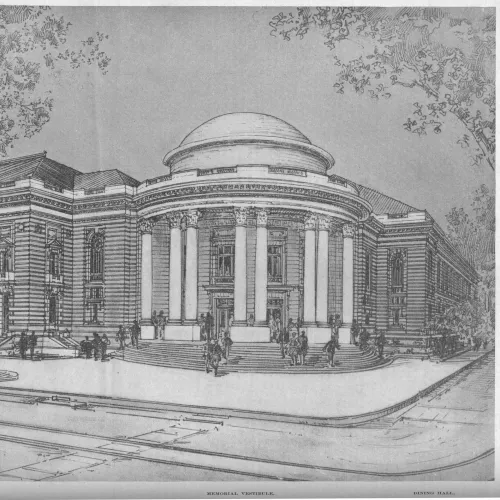

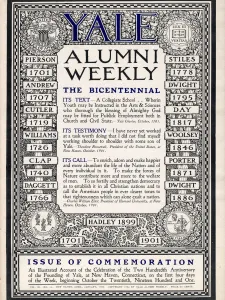

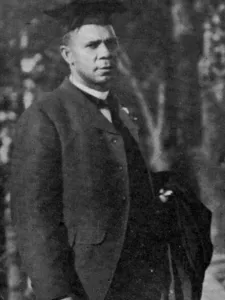

1901

Yale celebrates its bicentennial, using the occasion to welcome white Southerners back to the college. One speaker declares that Yale has “ever been proud” of its Southern alumni of the antebellum era, praising them as “eminent as statesmen, as soldiers, as scholars, and as divines.” Thomas Nelson Page is among a number of Southerners who receive honorary degrees at the bicentennial celebration.

Image above: Bicentennial Buildings, View from Corner of College and Grove Streets, Yale University Library.

Images below, left to right: Yale Alumni Weekly: the Bicentennial; Booker T. Washington, Delegate to the Bicentennial from Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute; Graduates Passing Hendrie Hall, Elm Street, During Yale’s Bicentennial Celebration; Commons Set for Dinner, Yale University Library.

1903

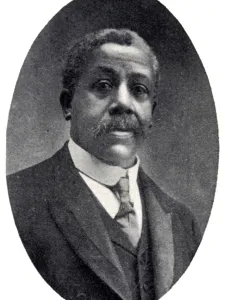

George W. Crawford graduates from Yale Law School, where he is awarded the prestigious Townsend Prize for oratory. He goes on to ascend the highest ranks of Black professional life in New Haven, practicing law in the city for decades and serving four terms as the city’s corporation counsel. Crawford establishes an NAACP branch in New Haven and is a longtime member of the Dixwell Avenue Congregational Church (formerly the Temple Street congregation). He serves on the boards of Howard University and, for over 50 years, Talladega College.

George W. Crawford (LL.B., 1903). The Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School. MssA C858 flat.

1903

Thomas Nelson Baker, born enslaved in Virginia in 1860, completes his second Yale degree, becoming the first Black person in the United States to earn a PhD in philosophy.

1904

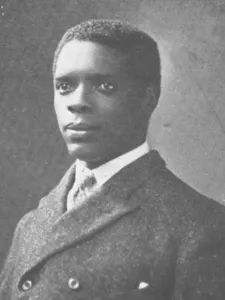

William Pickens graduates from Yale College. He goes on to teach at Talladega College in Alabama and at Wiley College in Texas and serves as dean of academics at Morgan State College in Baltimore. He helps to build the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, where he works for over two decades.

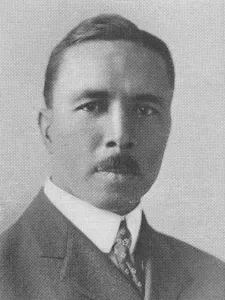

William Pickens, Yale University Library.

1905

Edward Bouchet graduates from Yale College in 1874 and earns a doctorate in physics from Yale University in 1876. He is the first Black person to earn a PhD in the United States. In 1905, he is turned down for a teaching position at Yale despite his sterling qualifications—six years of Latin, six of Greek, ranked sixth in his Yale class—and a ringing endorsement from Arthur W. Wright, an eminent Yale professor of molecular physics and chemistry. Over the next 14 years, Bouchet lives a peripatetic life, crisscrossing the country to hold teaching jobs in Missouri, Ohio, and Virginia. He becomes ill and eventually returns to New Haven, where he dies in 1918 and is buried in an unmarked grave in Evergreen Cemetery.

Edward Alexander Bouchet, Yale University Library.

1915

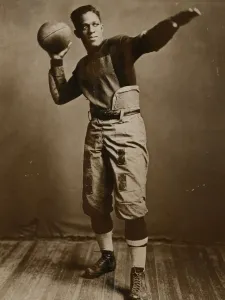

A Black student at Brown University, Frederick Douglass “Fritz” Pollard, plays football in the newly built Yale Bowl—the first Black person to do so. A halfback, Pollard must enter the field separately from the rest of his team to avoid hostile crowds. When he gets the ball, Yale fans yell racist epithets at him. Pollard goes on to distinguish himself as the first African-American player to appear in the Rose Bowl, the first African-American quarterback, and the first African-American head coach in the National Football League, among many other barrier-breaking achievements.

Fritz Pollard, Brown University Library.

1915

The John C. Calhoun Memorial Scholarships are established. Founded and funded by the Southern Club of Yale and the Yale Southern Alumni Association—with the blessing and praise of Yale’s leadership—the Calhoun scholarships are to be awarded to two Southern students each year. “The Southern Club has long felt the need of establishing a memorial of some sort to J. C. Calhoun, and it seems most fitting that the scholarships for general excellence in athletics and scholarship should be dedicated to this eminent Yale graduate and national statesman,” the Southern Club president declares.

1915 June 20

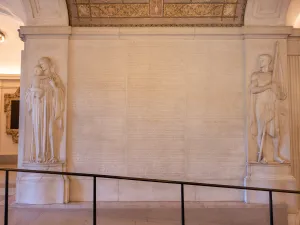

In an elaborate ceremony, the Yale Civil War Memorial is dedicated. It honors fallen soldiers from both the North and South and makes no mention of slavery.

The Yale and Slavery Research Project completes its study of Yale’s history here. The research team chose 1915 as the endpoint in part because the dedication of Yale’s Civil War Memorial was the capstone to decades of deliberate forgetting, both at Yale and in the country as a whole, about the reasons for the Civil War. Yale’s collections are available for other faculty members, scholars, and students to conduct further research on the legacies of slavery and racism in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Images below: Yale’s Civil War Memorial, Yale University Office of Public Affairs and Communications.

Our Forward-Looking Commitment

Continue to next section